In Activity #1 we examined surviving evidence about how coded rules or norms might have shaped who could or could not socialize, eat, drink, or shop at certain places in La Crosse. With the exception of the Palm Garden’s separate entrances for river traffic and town residents, Activity #1 mostly focused on La Crosse’s permanent residents. For Activity #2, we want to shift our focus to people traveling to La Crosse for work or leisure, and what exclusionary norms might have shaped travelers’ experiences at local hotels and motor lodges.

Lillian Smith Davenport’s 1941-1942 campaign to end exclusionary signage in downtown La Crosse (from Activity #1) hints at how unwelcoming La Crosse might have felt to people of color who visited the city in the 1940s. As someone who grew up in La Crosse, but had lived elsewhere for a number of years, Lillian may have had both an insider’s perspective as well as the ability to see La Crosse from a tourist’s or newcomer’s eye.

This tourist’s perspective of La Crosse as a place one might encounter exclusionary norms was echoed later in the decade by two Black union delegates who sued the Stoddard Hotel for unequal treatment based on race in 1946.

1947 Racial Discrimination Lawsuit Against Hotel Stoddard

In 1947, two Black American tourists sued the Stoddard Hotel for racial discrimination they experienced while in La Crosse for a conference. During the lawsuit, the manager of the Stoddard, John A. Elliot, corresponded with a number of people, including some friends and colleagues in the Wisconsin State Hotel Association. Decades later, the law office that had defended Hotel Stoddard donated the correspondences (among other papers in this case file) to the La Crosse Public Library Archives. To read how Elliot talked about the lawsuit, read this blog published by the LPL Archives in 2021:

“1947 Racial Discrimination Lawsuit Against Hotel Stoddard,” by Jenny DeRocher.

Towards the end of the blog post linked above, there’s a reference to the Green Book series that Black motorists relied on to help them find safe places to sleep, eat, and buy gas while traveling across the U.S. Although the Stoddard Hotel never made the list of recommendations for La Crosse, the Green Book guides published between 1957-1967 listed two places: Nuttleman’s Lodge Motel and the Linker Hotel. (You can see them both here on this page from the 1960 Green Book.)1 Taking our cue from the Green Book series, let’s look at surviving evidence about these two places.

Nuttleman’s Lodge Motel

There are two important challenges we have to keep in mind when using the Green Book series as a primary source. First, information about where it was safe to stop for gas or food or lodging was compiled through long-distance communication networks that made it impossible for any one person to fully verify every listing. The Green Book series was created by New York resident Victor Hugo Green, who was assisted by his wife Alma. Green was a postman, so one kind of communication network he was able to tap into for information was the National Association of Letter Carriers: fellow postal workers in other parts of the U.S. provided suggestions for his guides Charles McDowell, an employee at the Department of the Interior tasked with promoting cross-country tourism also provided information. And, as it grew in popularity, the Green Book also integrated suggestions from its users.2

The second challenge for using the Green Book series is that there may have been cases where business owners accepting Black travelers’ money did not necessarily equate to accepting the idea of racial integration. Some complicated evidence in a 1979 oral history interview with Mabel Nuttleman hints at the challenges Black travelers may occasionally have faced when following Green Book suggestions. Mabel and her husband Richard were the proprietors of Nuttleman’s Lodge Motel on Highway 16 from 1931 until 1962. Their lodge appears in the Green Book from 1960-1967. In her oral history, Mabel describes the lodge also being listed in AAA TourBook guides published by the American Automobile Association, and the efforts she and her husband went through to get it listed. So appearing in the Green Book could have been a comparable kind of business decision. But in the section below, Mabel’s recollections seem to suggest she had mixed feelings about Black guests staying at her motel.

To englargen these images in a new tab: Page 1 | Page 2

The Linker Hotel

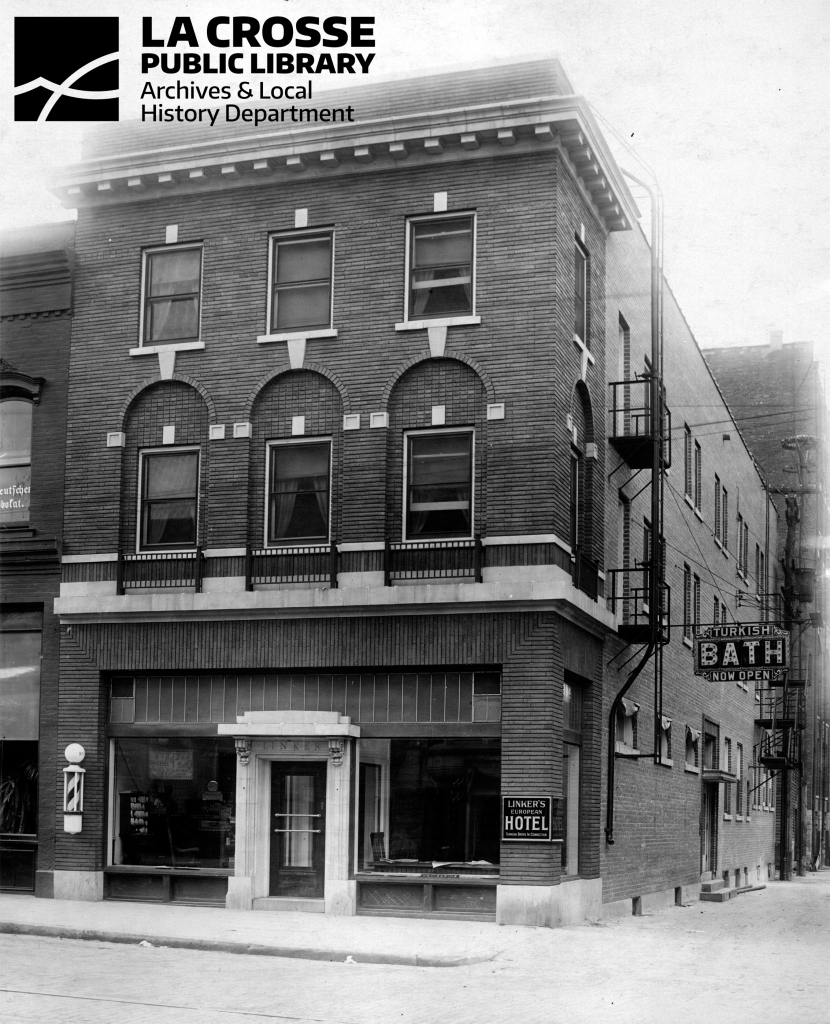

The other La Crosse location appearing in the Green Book series is the Linker Hotel. The Linker Hotel was owned by three brothers, George, Charles, and Henry Linker, who were German immigrants that came to La Crosse in the 1880s. Their business started as the Linker Brothers Barber Shop and Turkish Bath Rooms, located across the street at 3rd & Main streets. In 1915, the brothers purchased a building at 318 Main St. that had recently sustained fire damage. They completely remodeled the interior of the building, adding underground plumbing and Turkish baths. It opened back up as the Linker Hotel, Barber Shop, and Turkish Bath.

When it opened in 1916 with the new remodel, it was open exclusively for men. Salesman and other business travelers were the hotel’s targeted clientele. By 1919, plans were in the works for a new addition to the back of the building, with possible baths for women. However, no surviving articles confirm that this second set of bathing facilities were ever actually added. It is not until a 1937 ad that we see any sort of hint that the Linker Hotel allowed guests that were not male.

Over time, the Linker Hotel opened up to families traveling through La Crosse, which is confirmed by a 1946 newspaper article. It’s not clear how the Linker Hotel came to be recommended in the Green Book series. Unfortunately we are not aware of any oral histories or other sources that describe what the experience of staying at the Linker Hotel or using its Turkish Baths might have been like for patrons.

Guided Questions

- The sources we had to work with in Activity #2—letters and a judge’s ruling, Green Book listings, an oral history, newspaper articles—leave us with an incomplete picture of what it might have been like to navigate potentially exclusionary norms in La Crosse as a traveler in the early-mid 20th century. What conclusions are you comfortable drawing from this evidence? What questions are you left with?

- In August 2021, we explored how people living in the La Crosse area marketed (or “boosted”) our region as a tourist destination. The sources in Activity #2 shift the focus to a visitor’s eye view of La Crosse. How do you think the sources for this activity could fit into a history of tourism in La Crosse? What kinds of stories about La Crosse as a tourist destination could they potentially help us tell?

ENDNOTES

- Green Books can be viewed online here: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book#/?tab=navigation

- Much has been written about the Green Book series, both before and after the 2018 movie of the same name introduced this history to a wider audience. For History Club purposes, Encyclopedia Britannica’s article about the Green Book series is an accessible way to get up to speed: https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Green-Book-travel-guide. We used this source to confirm the details about the communication networks Green tapped into to compile recommendations about places to stop, shop, and stay. We also think the later parts of the entry describing white business owners’ complex reasons for appearing in the guide and how the limited number of people of color living in places in the Upper Midwest might have made it harder to make useful recommendations could be applicable to the situation in La Crosse. For a lengthier explanation that examines women’s contributions to the Green Book series, see this web page from the National Park Service: “Green Book Historic Context and AACRN Listing Guidance.”

This month’s History Club meeting will be on Thursday, May 30, 2024, from 5:30-6:30pm at the La Crosse Public Library in the Archives & Local History Department on the 2nd floor of the Main Branch. RSVP here.