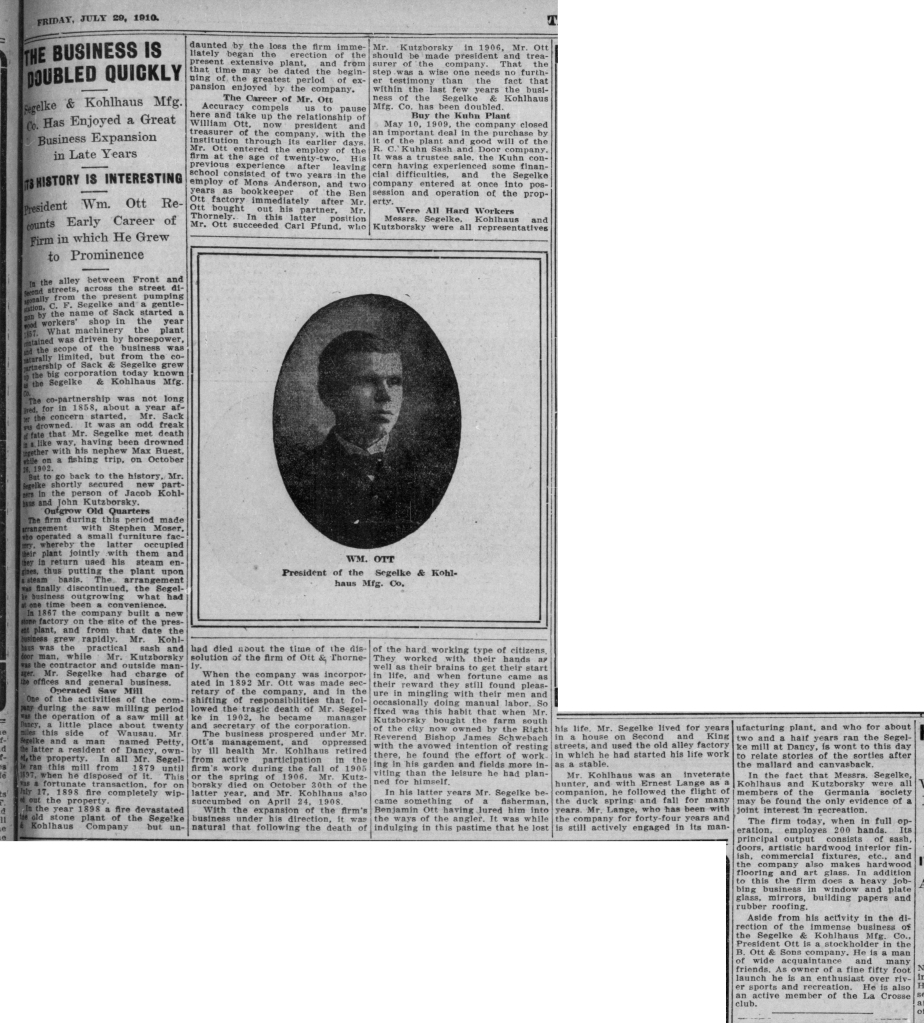

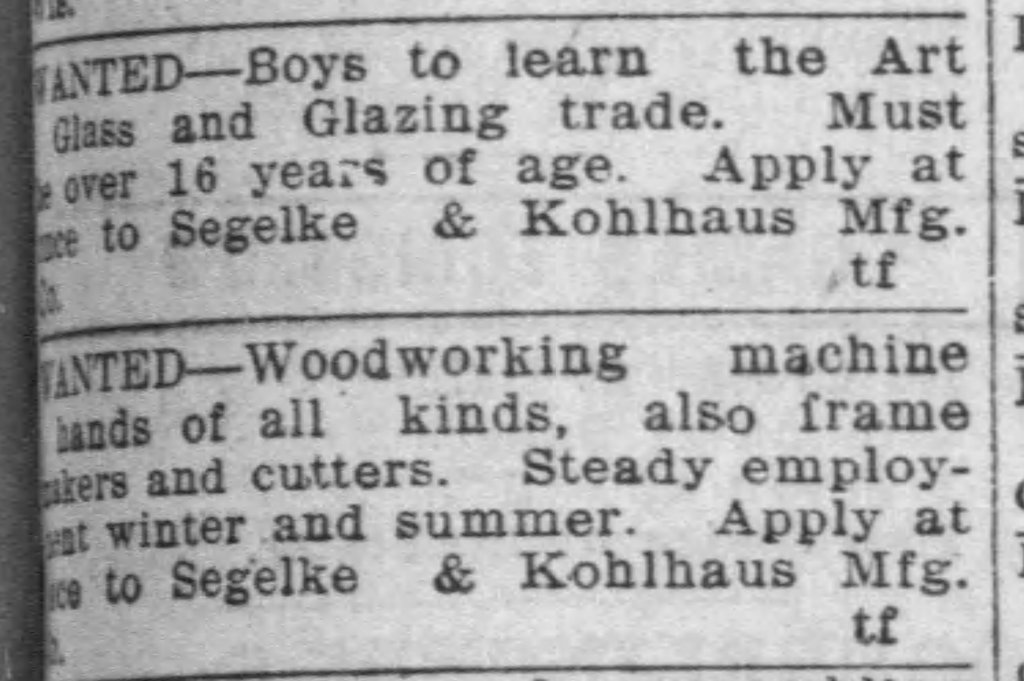

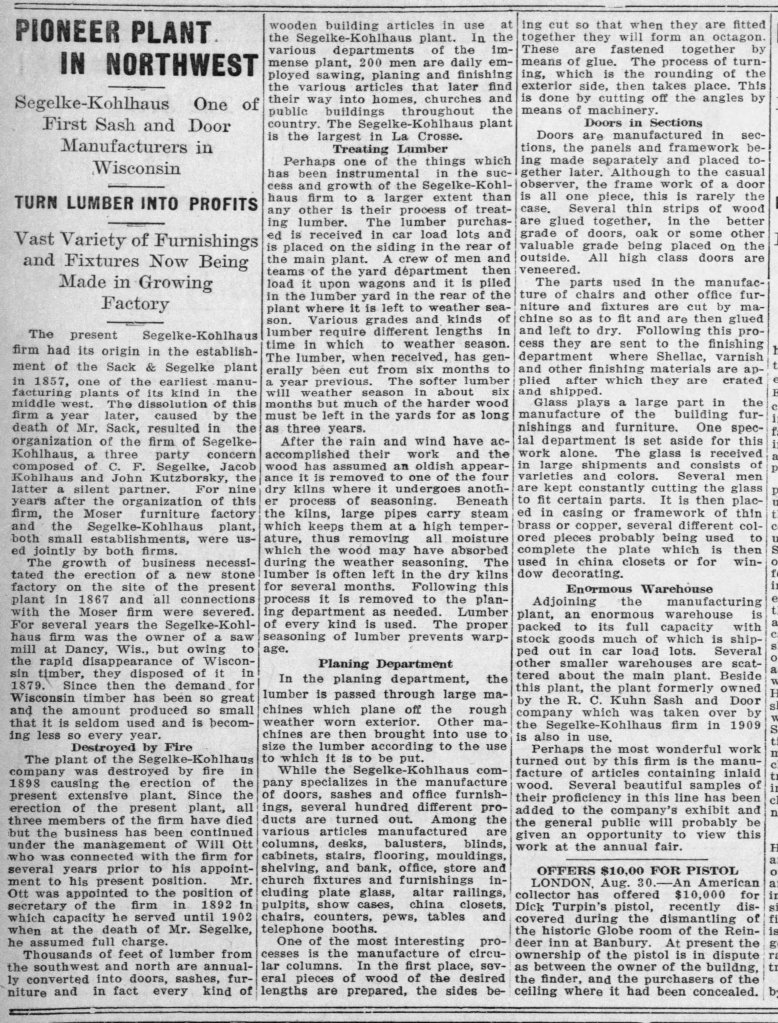

This March, we are looking at the Segelke Kohlhaus Manufacturing Co, (S&K). In Activity #1 we focused more on S&K’s history and what its products were like. Now in Activity #2, we want to turn our investigation to the people who made both the corporation and the products. In other words, we now want to look at surviving sources through the prism of labor history.

What is Labor History?

As the editors of the scholarly journal Labour: Studies in Working Class History describe it, Labor History is focused on asking and answering questions like: who does the work? under what economic and political terms do they do the work? Labor history also focuses on using available primary sources to piece together what the “world” of people who worked in particular industries might have been like: the physical conditions in the places where they made products and performed services, the social conditions in which they formed bonds with coworkers, organized mutual aid societies and debated unionization, the cultural conditions in which their identities as laborers were shaped by their pride in the objects they made or their alienation from the managerial class.

Labor history overlaps significantly with another kind of history we often explore in History Club: social history. Both approaches seek to recover what is knowable about the everyday lives of people who didn’t have the leisure time and means to produce memoirs or donate documents to archives. So labor history looks for ways to explain what it was like to do particular kinds of work, how people defined the meaning and/or value of the work they did, and how they reacted to the circumstances they did their work in.

How do surviving sources shape how we can study labor history?

While looking for available primary and secondary sources for this month, we quickly discovered that the perspective of the employee’s of S&K are not well represented in the archives. Historically, working class employees rarely created many records, but sometimes little snippets sneak through the classist, racist, sexist, colonialist foundation of early U.S. record keeping. In La Crosse, we’re lucky to have had Howard Fredericks interviewing folks in the 1960s who worked in local early 20th century factories and the surviving UWL Oral History Program collection. But few other sources exist that show working class perspectives in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

One source that allows us to peek into the reality of La Crosse’s largely working class population are newspapers. Newspapers give us information on what was happening in the community, and the way that the media shapes the narrative can speak volumes, if you read the articles with a critical eye. Sometimes newspaper articles don’t give us the worker’s perspective, but report that there was a strike and the terms that were being negotiated between a company and a union. Sometimes a reporter interviewed an employee, which appears on the surface to be a glimpse into their perspective, but is still funneled through the voice, experiences, and biases of a reporter who is not a factory worker.

The Activity

With this understanding of what labor history is and how surviving primary sources may not fully present workers’ perspectives, let’s look at some primary sources written largely during the time that S&K was still operating (1857-1960) and analyze them from the labor perspective. Below, we’ve prepared some questions to consider as you read each source.

One last note: part of labor history also involves considering what else could be happening in the world that impacts someone in their everyday life. For example, during the Great Depression in the 1930s, fewer houses and buildings were constructed—which in turn would have likely impacted S&K’s profit, and in turn could have been the reason employees were laid off. During wartime, important materials like wood, lumber, and metal were rationed, and many U.S. manufactures saw huge profits if they were contracted by the government to produce war materials. Many factory workers before WWII were men, but after WWII this changed. While reading the newspaper sources we’ve assembled for Activity #2, try to consider what contextual events and eras could have shaped the experiences of the workers.

Guiding Questions

- Who wrote the source you are looking at? What might their background be? What biases could they have?

- What would the author’s sources be?

- What is the purpose of the source you are reading? For example, is it a historical overview of the company? Is it an advertisement? A news story alerting the community of an event or milestone?

- In what terms are the workers talked about, if at all? What are some adjectives used to describe them? What language is used to describe the work they do?

- Do you see any examples of the workers being erased from the narrative completely? For example, does the author give the company as an entity credit for work done by individuals?

- Can you think of any contextualizing events to explain any details or language within these newspaper articles?

Sources

Click link below to enlargen articles in new tab.

Article 1 | Article 2 | Article 3 | Article 4

Click link below to enlargen articles in new tab.

Article 1 | Article 2 | Article 3 | Article 4 | Article 5 | Article 6 | Article 7

Click link below to enlargen articles in new tab.

Article 1 | Article 2 | Article 3 | Article 4 | Article 5

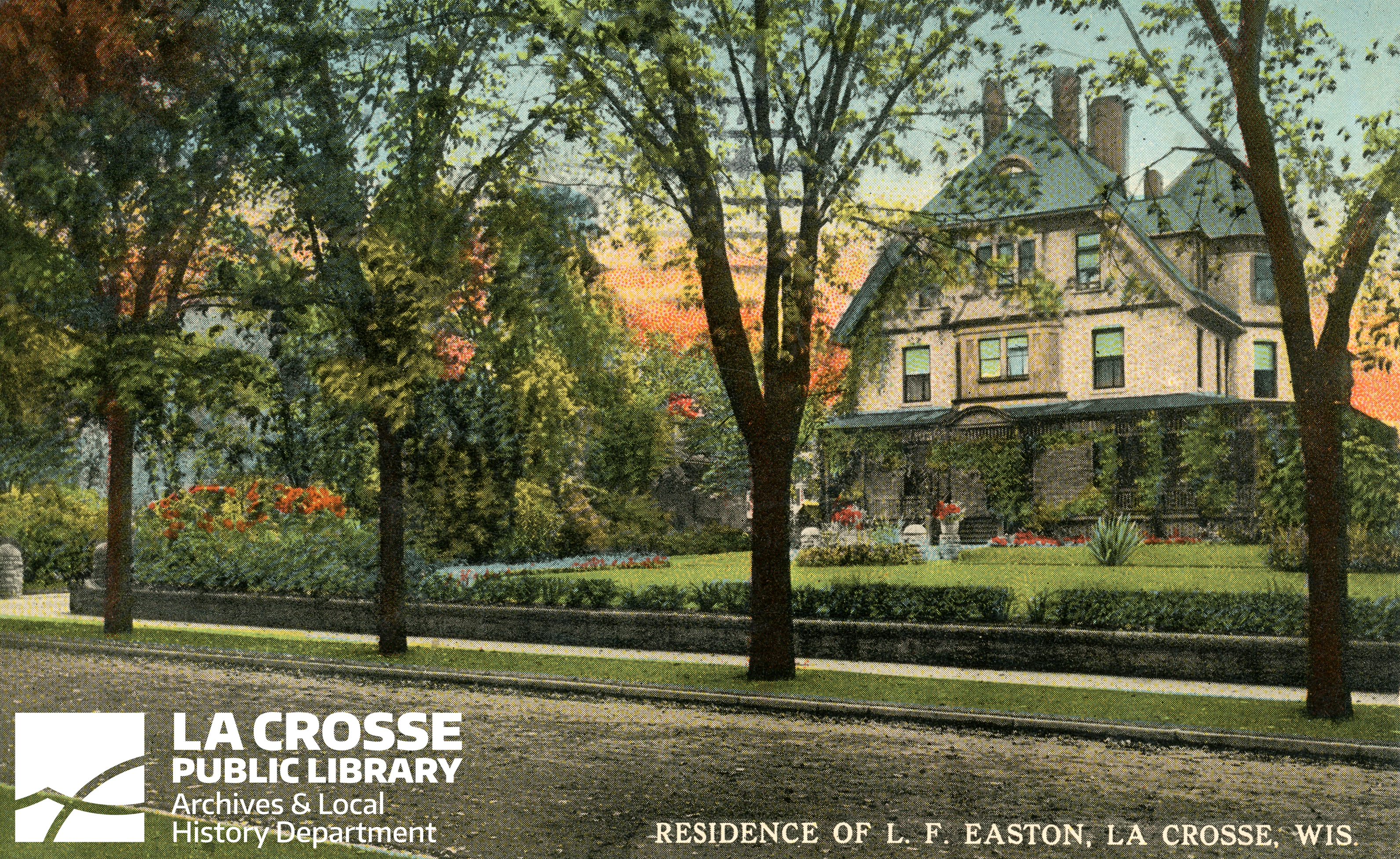

This month’s meeting will be held on March 27, 2024 at 5:30-6:30pm (RSVP here). At our meeting, we will look at photographs of some Segelke Kohlhaus woodwork in houses still standing in La Crosse today, and try to think more about what an S&K employee’s world may have looked like.