This month’s activities were inspired by some of the things we learned during our March and May activities. In March, we examined the working lives of skilled craftsmen who made wooden architectural elements at the Segelke & Kolhaus (S&K) factory in La Crosse (1857-1960). This got us wondering about what we might figure out about the skilled laborers who cut down and transported the trees that ultimately made their way to the S&K woodworkers. May’s discussion of exclusionary norms included the Palm Garden restaurant, which had segregated entrances and spaces for community members and “river traffic,” which included lumber industry workers. During those History Club meetings we found ourselves talking about the people whose labor contributed to our region’s economy, but remained on the margins.

So this June, we are going to take a look at the life of a lumberjack and other lumber workers in the broader La Crosse area, circa 1850s-1900. First, we’ll look at the history narrative that has been told about lumberjacks for the past 100-150s years. Then, we’ll look at surviving sources that suggest what a lumberjack’s day-to-day life may have actually looked like, in an attempt to figure out what we can actually know about folks working in the lumber industry and how this information does, or does not, fit in with the narrative we’ve been taught in our local and regional history.

Before we start, check in with yourself (it’s okay to have no answer for these questions!):

- What have you learned/heard/read, if anything, about the lumber era (c.1850-1905) in Wisconsin? In La Crosse?

- How important do you consider the lumber industry in Wisconsin’s history? La Crosse’s history?

- When you picture a Midwestern lumberjack from the 1800s, what do you picture? Where does this image come from?

What the Sources Tell Us About the Lumber Industry In Wisconsin & La Crosse

LOGGING

- Lumberjacks, loggers, or choppers cut down trees in the forest.

- Swampers trimmed trees after they were cut down, branded the logs with the owner’s mark, and cleared the path to transport the logs to the river.

- Sawyers sawed the trees down into logs.

- Skidders transported the logs to the river.

- Drivers or drive crew piloted the logs down the river, some in boats, but many riding the logs to steer them and prevent jams.

- Laborers worked in the sawmills along the rivers, using dangerous machinery to make logs into lumber.

- (Note: the title “Lumberman” was typically used exclusively for the capitalists who owned a lumber camp or sawmill, not the skilled laborers working in the lumber industry)

Sources for these definitions:

Jerry Apps, When the White Pine Was King (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2020), 22-77.

Frank Hartman, “Life In a Lumber Camp,” in La Crosse County Historical Sketches Series 3 (La Crosse County Historical Society, 1937), 18-24.

In addition to the above jobs, the lumber industry also required people to work as cooks, blacksmiths, payroll clerks, and teamsters to keep logging operations running smoothly. Because many of these jobs were seasonal, sometimes one person could spend their year doing three different jobs. They might work as loggers in the winter. Then, they had options. As the river melted in the spring, they started the log drives down the river to the sawmills. Some log drive crews had as many as 100 employed, so for loggers who were especially sure-footed and willing to risk the dangers of driving logs, a drive crew was one option. Another option was to go into town and work in a sawmill. As logs arrived en masse, the sawmills hired more laborers to transform the logs into lumber. Other loggers were primarily farmers who needed a steady winter income, and they would go back to their farms for the spring, summer, and fall.

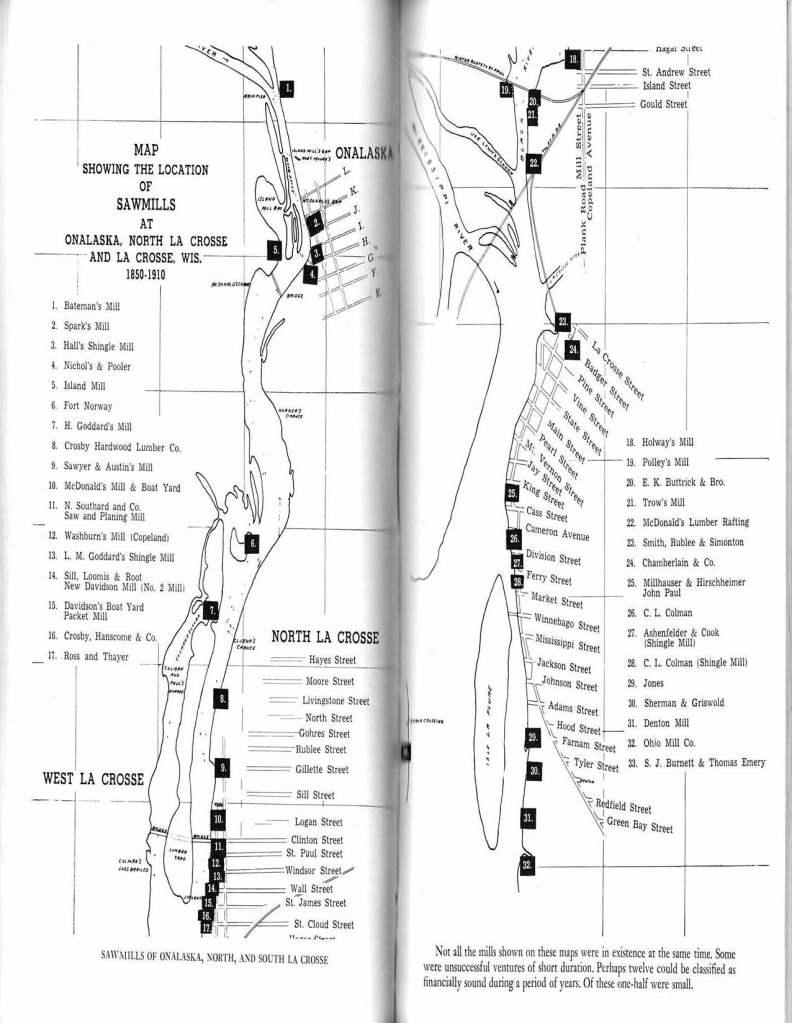

It was in these off-logging-season months where lumber industry workers would flood sawmill towns like La Crosse. Between 1850 and 1910, the Onalaska-La Crosse stretch of the Black River and Mississippi River was home to over 30 sawmills.

The following sources were written by two men who worked in various jobs in the lumber industry. The authors wrote up their recollections afterwards, ca. the late 1920s-1930s, and they were subsequently published in Series 3 of the La Crosse County Historical Sketches in 1937.

- “Life In a Lumber Camp,” by Frank Hartman, who worked as a clerk in a lumber camp in the 1880s. In this chapter, Hartman walks us through the different jobs within just the lumber camp.

- “Memories of Lumbering On the Black River,” by Charles P. Crosby, who worked in a lumber camp and on a drive crew.

SAWMILLS

Between 1850 and 1905, the Onalaska-La Crosse stretch of the Black River and Mississippi River was home to over 30 sawmills.

Click here to enlargen image in new tab.

While we have no first-hand accounts of skilled laborers in the sawmills, we have sources that show the sizable economic impact of this string of sawmills. Two surviving statistical records from 1890 (the beginning of La Crosse’s largest profit years in the lumber trade) are:

- The Board of Trade Reports for La Crosse (page 18) show about 4000 people in the city worked as loggers or in saw mills.

- In the U.S. Census aggregate book of Manufacturers, Wisconsin reported 32,755 people employed in the lumber industry. This was the second highest, behind only Michigan, who reported 46,592 employed people.

Click here to enlargen image in a new tab.

Together these numbers suggest that roughly an eighth of the laborers supporting Wisconsin’s lumber industry were based here in La Crosse. However, we do want to stress that these are not exact numbers. The Census takers would have traveled through Wisconsin in June of 1890, so they would not have been able to record information about the residents of (then empty) lumber camps. And we are unsure what time of the year the Board of Trade compiled the information for their reports.

What Historians Tell Us About the Lumber Industry In Wisconsin & La Crosse

When we study history, we must look at what historians from previous generations decided it was appropriate to say, especially if their beliefs and characterizations were repeated by subsequent generations of historians. This phenomenon of inherited narratives can, in turn, shape stories about the past that we all hear over and over. It is the responsibility of each new generation of historians to revisit primary sources and secondary sources and identify any misperceptions that no longer apply, are one-sided, or biased.

For example, in August 2022 we did some of this questioning of inherited narratives when we examined how and why Nathan Myrick has consistently been cited as the founder of our city. Looking more into La Crosse’s early history, it is easy to find there were a number of Ho-Chunk residents living here long before Nathan Myrick came. There were also other white colonizers (like John and Fredericka Levy) who came around the same time as Myrick, but stayed in La Crosse for their whole lives becoming long-term, dedicated community members.

All of this got us wondering: how are lumberjacks and other lumber industry workers remembered in the history of the La Crosse region? How did early historians talk about them, and how do more recent generations of historians talk about lumber workers? Are there any potential adjustments to the narratives about them that seem necessary, based on our sources above?

Below are four major histories of La Crosse. Each has their own focus, which you should take notice of as you read through. Below are some guiding questions you can think about as you read these characterizations of lumberjacks, log drivers, and sawmill workers, if you would like.

Guiding Questions

- In what ways are these narratives from secondary sources similar? To what extent is there a recurring, inherited, narrative about lumber workers?

- In what ways are these narratives different?

- What can you tell about how the time period these sources were written in may have impacted their content? How does the identity of the author of each source impact their content?

- After reading, what are you still wondering about the working and living conditions of lumberjacks?

- In what ways is the information we listed above included or left out of these sources?

Source 1

In an undated source titled “The Black-River Boom,” author Hannibal Plain wrote about men who worked the log drives on the river:

“It is a life tending strongly to indolence and improvidence, and yet, often is exceedingly laborious. The “rivermen” were jolly fellows usually, given too much to meeting at the saloon; frank, independent, and proud of their physical strength. They worked when they worked, and when they eased off they didn’t do anything. When the winter closed the river, they went “into the woods,” that is, they went as choppers to the pineries farther north.”

Source 2

Likely a half century later, two early La Crosse historians, Albert H. Sanford and H.J. Hirshheimer wrote in Chapter 6 “Influences That Built the City,” in their book A History of La Crosse Wisconsin, 1841-1900:

“The second force at work in the progress of La Crosse was the Black River pinery, which began some thirty miles above La Crosse. This influence may be seen as early as 1846 in the statement by Mrs. Levy that her husband had found the Black River trade good the year previous. Myrick enumerates eleven mills on the Black and its tributaries in 1848. The equipment of these mills and the food and clothing of workmen were supplied from the outside. The overland route to the pinery from towns farther east and south was most difficult; the water route via the Mississippi was much easier. Since the Mississippi River boats could not ascend the Black River, the cargoes were unloaded at La Crosse. So there came to be businessmen here who stored and forwarded goods for a commission, and others who bought supplies from down-river towns and resold them to the Black River lumbermen. Similarly, the end of the winter’s logging in the pinery brought to La Crosse the lumberjacks with money to spend.”

Pages 52-72 of this book walk the readers through a number of industries, businesses, schools, churches, and early Euro-American colonizers that together defined La Crosse in the city’s early history. At the end of Chapter 7, “La Crosse In the Eighteen Fifties,” Sandford and Hirshheimer wrote:

“The picture of La Crosse so far drawn in this chapter presents many admirable features of its life in this decade. There was another side, however, that must be shown. In these years, gathered at La Crosse, a frontier town and place of transit, many ‘tough’ characters, both men and women. Besides, there was a certain element among the lumberjacks that came in the spring to spend the winter’s earnings in a wild debauch [sic]. This was true in varying degrees during the lumbering days of La Crosse, as in other river towns.”

Source 3

In the early 2000s, historian Bruce L. Mouser wrote a book on the Black American population in La Crosse in the second half of the 1800s called Black La Crosse, Wisconsin, 1850-1906. In Chapter 6, “From Trading Post To Frontier Boom Town, 1850-1865,” Mouser outlines the industrial and cultural opportunities in La Crosse that attracted immigrants and migrants. Like Sanford and Hirshheimer, Mouser summarizes the businesses and early Euro-American colonizers who defined La Crosse during this period on pages 111-117. Then he wrote the following:

“Balancing these honorable characteristics were several questionable ones. As a frontier town where shipping, milling, and railroading increasingly dominated, La Crosse had the feeling of a book town, populated by hardy and independent people. The large number of hotels, eleven in 1856, exemplified the transitory nature of a significant portion of its population. Lumberjacks worked hard in the pineries along the Black River and they descended upon the town during the weekends and relaxed as only lumberjacks were able. Barroom fights, brawls, knifings, public drunkenness, and gambling were common, and a large number of ‘whorehouses’ became a continuing feature of the town and a part of the local lore.”

Source 4

Published very recently in 2020, When the White Pine Was King, author Jerry Apps covers the history of the Wisconsin lumber era. While La Crosse is not a focal point, Apps does mention La Crosse a few times. In general, however, Apps uses a few examples of Wisconsin communities to represent the overall state history. Chapter 7 is called “Life In A Sawmill Town,” and he wrote:

“The liveliest time of the year in the sawmill towns was spring, when the lumberjacks and river drivers returned from the woods and rivers with money in their pockets and a thirst for a rip-roaring good time. The saloon and the gambling establishments thrived during these celebration days that went on until the men ran out of money. Brothels did a lively business as well. Author Michael Edmonds wrote about a brothel owner near Marinette [WI]: ‘Each spring he employed a woman, Mrs. Kassidy, to hire prostitutes in Chicago and Milwaukee in time for the arrival of the lumberjacks; some years he employed as many as sixty-five women.’ Prostitutes weren’t found only in Marinette; Green Bay, Superior, Ashland, and Hurley—almost every mill town had its red-light district.”

After we’ve had a chance to examine these two different perspectives on the lumberjack lifestyle–recollections of men involved in the work themselves, and how historians subsequently characterized lumberjacks’ work and leisure–we can discuss what we think of these inherited narratives at our June 19 meeting (RSVP here). Are there any alterations, updates, or reframing it would make sense to do for the history of lumberjacks in the La Crosse region given the full set of sources we had access to in this activity?